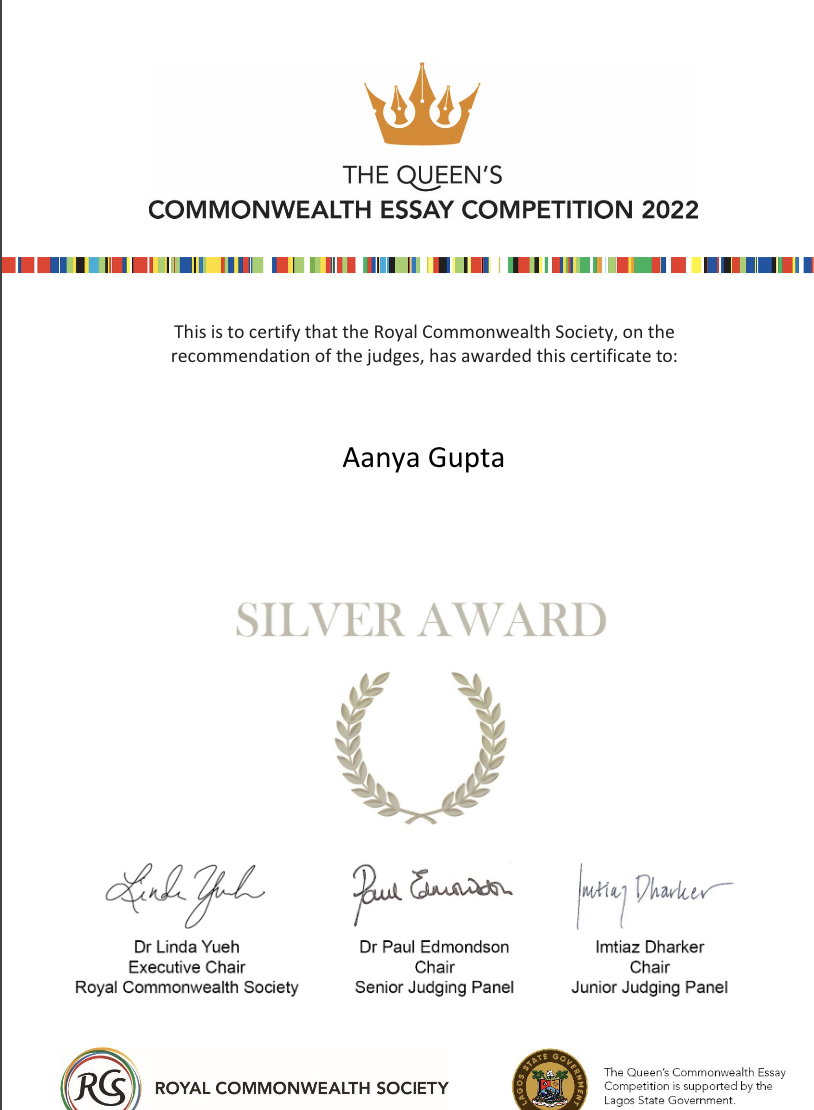

Won Silver Award in the Queen’s Commonwealth Essay Writing Competition, 2022.

Topic: Her Majesty The Queen was born in the twentieth century, a period that saw enormous social change driven by visionary and committed leaders. Reflect on an inspirational leader from this period.

Pre- Note: This account, although fictionally compiled, is based on true events. (References at the end). Bhanwari Devi was an illiterate woman, and this story begins, and goes on to end, with her.

“It was dusk. My husband and I were working in our fields when they started beating him up with sticks. There were five of them.”

I can still smell the husky scent of wheat, strands which brush against my face, my hands, my legs. They tickle my cheeks and make me blush as I reap the last of the crop.

I close my eyes, just for a moment, and when I open them again I am not surrounded by the wheat, but by these men. They do not speak, but signal to each other and grunt in sluggish, monosyllables. Two of them hold Mohan down, while the other three grab me and scourge their fingers across my exposed ribs.

“Let him go! Please! He has done nothing wrong! Have mercy-”

Before I know it my palla is wrenched off my head, and the lehenga jerked off my trembling body.

I remember sinking my teeth into the dirt, shovelling down the pain by a mouthful. I scream as they rape me, one by one, one of them from my buttocks. They go in again and again, and one lasts for so long my genitals squirm with the excruciating pain of the ordeal. I don’t know when I felt it go wet or hard, but there was no pleasure, there was just this nagging below my waist, my waist which my husband had caressed what seemed like a lifetime ago-

A lifetime. I scream as they beat him with sticks, beat him bloody and unconscious. I scream as they use my body one, twice, three, four times. It was the Gurjars, those two, who took turns, one by one while Ram Sukh held me down.

I had heard them talk about it, the villagers.

I knew what rape was.

And so I screamed.

***

It is late, but I am not done with my History project. I reach towards my coffee, but the cup is empty. Robert Frost did not lie when he said he had miles to go before sleep, and so I sit up straight and peered dejectedly at the computer screen.

We are supposed to reflect on a case where a fundamental right was broken. The last on my list included “Rape”. A Wikipedia page pops up. Bhanwari Devi, it reads.

Although it is late, I open up Bbc news, and begin reading the article by Geeta Pandey.

“An unlikely heroine”.

As I read, I cry, and after I have cried, I sleep.

***

As a child, I vaguely remember the sindoor being crushed onto my scalp. I wasn’t ever asked, or told, what “marriage was”. I’m sure my “husband”, a mere boy of eight or nine, wasn’t ecstatic at having a child bride either, now that I think of it.

One morning, my mother awoke, and massaged coconut oil into my temples and whispered in her most soothing dialect. We were kumhars, I was told. I was a good girl now, they said. They said, and I listened.

I listened to my husband and moved to Bhateri. I listened to the elders and had children with him.

I forgot to listen to myself those days. Later, someone told me that I was just a teenager. What is a teenager, I asked, the word thick and unfamiliar on my tongue. I was a married woman, afterall.

***

I scream long after the men are gone. After I am done screaming, screaming till I cannot scream anymore, I stumble to an upward position, and walk. I am guided only by the half moon as I make my way painstakingly across the fields. I can feel my matted hair sag under the weight of Mohan’s bloodstained saafa. There was nothing else to cover myself with. I had tied that turban, just this morning. I tried to increase my pace, until those dreadful three kilometres were done, and I had reached Kherpuria.

As I banged on the door of the police station, a male policeman took one look at me and averted his eyes. By the time a woman could come to attend to me, I was in no condition to talk to her. What would I have said anyways? I had said too much already. I knew that.

She took my white lehenga, which was now a murky crimson, which I gave reluctantly because their seed was still on it. She looked at it, and whispered to the attendant. I didn’t want to overhear, but I did. I couldn’t close my ears, or my mouth. Not even if I wanted to.

“Shouldn’t we swab her?”

“We can’t without the Magistrate’s Order.”

“Then we should get one. You know it’s against the law if we delay-”

“The Magistrate won’t give permission for a vaginal swab right now. It is late. Very late. We have no way of immediate contact beyond working hours!”

“What should I write in the report-”

The voices fade into the background.

Who was Bhanwari? I used to know. I don’t know anymore.

***

The rays of the sun tease open my eyes. Last night’s story comes rushing back to me as I crack open my laptop.

I read about how she was ostracised for the work she did against child marriage, for the social boycott imposed on her, just for working with the Women’s Development Project in Rajasthan. I read about how she walked to a police station hours after being raped. How they refused, in the hospital, to examine her without a female attendant being present.

It is so easy, in our urban society, to talk about gender inequality, I realise with a start. It is so different in rural areas. The rules they have. Their traditions. Their divides.

How do we start the change there? It says she insisted a Kumhar Caste Panchayat be formed, to represent herself, to give back her rightful place in society.

Is there truly a place for people like Bhanwari Devi?

***

I sit cross legged on the floor of my hut, the dry mud used to set the floor now perfectly caked. Sitaraman, our postman, sits in front of me, sweating with anticipation as I urge him to write faster.

“Address it to the Sub Divisional Police Officer, you hear me? And ensure my station is written clearly on top, Bhanwari Devi, Grassroots Worker.”

“Tell him that Ram Karan Gurjar is going to get his nine-month old daughter married on the eve of Akha Teej! Talk about how many other Gujjar families are following in his footsteps.”

“I am writing, Devi,-”

“Ssh. Ask him to accompany me next week to Ram Karan’s house to stop this terrible thing from happening.”

Once I have tortured Sitaraman to post the letter, I go on my daily round of the village. As an established saathin, a friend, a worker, I have finally found a voice. It is not perfect, nor especially powerful, but it is something.

And finally, I can speak. I hope that soon, I can also do. What was that saying? Actions speak more than words.

No.

The “right” actions speak “louder” than words.

***

I scrolled through the facts:

1985, Bhanwari Devi became a WPD worker.

1992, 5th May, the police and her stopped Ram Karan Gurjar from marrying off his infant daughter.

1992, 22nd September, she was gang raped.

1992, 25th September the court case started.

The evidence presented in the court was as follows-

- The semen of five different men were indeed found in Bhanwari’s vaginal swab and upon her lehenga (long skirt)

- There was not even a single match between any of these five semen traces and the semen of any of the five accused (including two who she had accused of raping her and three whom she had accused of pinning her down).

- Bhanwari’s husband’s semen was not found in the vaginal swab (none of the five semen traces were his).

In 1995, the court ruled against Bhanwari Devi, not having found a sample match. This raised a great uproar. The court even went so far as to suggest that her husband couldn’t have just “passively watched” her being gang raped.

However, Bhanwari’s voice, and her right actions, won her prestigious awards and she soon became the face of women’s rights in rural Rajasthan.

Visionary. She didn’t know that word, but I did.

Bhanwari Devi is the unknown woman behind the Vishaka Guidelines, the country’s first guidelines for sexual harassment in workplaces. An illiterate, uneducated woman from rural Rajasthan, who struggled to find her “place” in society ensured that so many women find theirs.

Today, most of the girls in Bhateri go to school, including those in the family of her alleged rapists, who live next door to her.

Bhanwari Devi leaves the door unlocked at night.

I ended my project with that. Bhanwari Devi wasn’t a visionary. She was just another married woman, who envisioned. She envisioned a new life.

Was it better?

***